A short story by Peter McBride

It was a still, chill night. The moon stood high and full,

making the village almost as bright as day but drained of all

colour. I walked home across the silver sea that was the village

green and there in the centre I saw an old man. He was hunched

low over a strange device which reminded me of a sundial.

I stopped, overcome with curiosity, and stared in silence. What

was that device, and who the man? Was it indeed a man, and was he

yet alive, for he moved not.

"Tis a moondial," he said at length, in answer to my

unspoken question. "Have ye not seen one ere now?"

"No indeed," I replied, "Does it tell the

time?"

"Time!" He gave a dry cackle, "Aye, it tells the

time. And time will tell of it."

He raised his head, and a grey face, deeply lined, looked up at

me from within the blackness of his hood. "Time! Aye, 'tis

time. Sit ye now, if ye have time!" He laughed again at some

irony that only he understood, and waved a withered hand to the

ground opposite him.

I sat cross-legged on the silver grass and watched the moon-dial

tell the time and listened to the old man tell of Time - and

Magik.

And this was what he said....

1

"Time was when Time was not, nor Death, nor

Life as you would know it. And the Red Moon lay high above,

bathing the world in its ruby light. Magik there was in that

light and in all upon which it fell.

But the Red Moon did not enjoy sole sovereignty of the skies. The

Sun shone then as it does in these latter times, and when it rode

through the heavens, its fiery brightness overlay the Moon's cold

crimson light. Only when the Sun passed below the land did the

Moon reign unchallenged. Yet for long ages the world grew and

lived in harmony, the sun's coarse vigour tempered by the pure

magik of the Moon.

We were young then... Young? No, not young, but ageless, for

there was no Time and therefore no ageing. But we had all the

strength and impudence of youth, we who had being but not form.

We who called ourselves the Ten that were One, the Guardians of

the Timelessness.

And the world was reflected in the thoughts of we Ten, and our

thoughts were reflected in the world. Each took an aspect as his

own; one delved into the mysteries of the deep seas:

another allied his powers with the birds of the air; a third

found fascination in rocks and running rivers; and there was one

who contemplated the Heavens above. Yet did we study the world or

were we its designers? Who should tell? The question was of

little import then, when what was, what could be. what should be,

was all one. Neither did we question our right to lordshop. We

knew no limit to our powers, and we set no limits. Ha! So wise

and yet so ignorant.

2

Throughout the Timelessness, for that was how we

named it when Time afterwards came upon the world, the Yellow Sun

and the Red Moon circled, each in its chosen path, high above the

world. Then the Astronomer began to speak of Change and the

passing of Time.

'Observe the Sun and the Moon,' he said. 'See how their paths cut

across each other as they track through the Heavens. I have

marked the junctions in our mind. Look within and you will see

that a collision must come. The Gods are set on courses that must

lead them to do battle.'

And we others looked, and saw, then shied with horror and said,

'Do not think that thought! This must not be!'

Ah! The meddling fool! He should have known that some things are

best left unknown. But the thought had been made and could not be

unmade.

And so it came to be that the Sun and the' Moon met in the skies.

The Moon standing before the fiery majesty of the Sun, striving

to make the world its own, letting only its red light shine upon

the world. The Sun in its fury hurled its fires into the Heavens,

dragons of flame lashing angrily around the Moon, until that

lesser god gave way and slipped aside, paled and weakened by the

contest.

They parted and the Moon seemed to regain its former strength and

cold glory but at length its path drew once more close to the Sun

and again they did battle in the Heavens above, and again the

Moon withdrew, its light less brilliant than before. And

throughout the Timelessness-that-was-ending, the Moon would

return to do battle ever and anon, and each time it gave way its

red light growing paler and less bright.

Mayhaps, if we had conjoined our powers, we could have guided

those heavenly bodies into new and safer courses. But we did

nothing, only stood by like helpless maids, and wrang our hands

in horror, while the Astronomer observed the conjunctions and

measured the Ages. He chronicled the cycles of the Sun and called

them years. He observed the cycles of the Moon and called them

months. And with the fading of the Moon came that alternation of

light and dark that he called Day and Night. Thus, Time was born,

and Time passed.

That harmony was no more, that once the world had enjoyed. Magik

faded in the crude vigour of the Sun's light, and thrived only at

night when the Moon still held sway. Men walked upon the earth

and turned their faces against magik.

They built machines and fortresses, and through them fought for

mastery over the world.

We, that had been the Ten that were One and had existed only in

mind and magik, were One no more. Now we were truly ten, and

oftimes thereafter, as Time crept upon us, we took human form.

Thus wise we went among the world and strove to restore and

rebuild the magik that was fading. We breathed our powers into

the mantle of the earth, wove charms into the fibres of the

plants that grew in the wilds. We entered the cities and

installed ourselves on the Councils of men and sought to lead

them from merchandise and machinery, back to magik.

Ah, what vain effort went into our attempt to staunch the flow of

Time and magik. Yet not all of the ten mourned the passing of the

Timelessness. He that had measured and named Time, that was

himself then named Father of Time, looked upon the new world and

was glad, for in Time he had found Death, and in Death he had

mastery of Life.

We other nine were deeply troubled and met in council to debate

amongst ourselves how best we could return our world to the

Timelessness. For with the passing of time and the fading of

magik our dominion over creation was fast slipping away.

But there was no return, for Time was, and all things must end

with the passing of Time, except Time itself.

We Nine came to know this, and sought for other ways to reclaim

our mastery. Long we wrestled with the mysteries of Time and

Change, then one who had steeped himself in the science of

Physics spoke up in that council and spoke thus;

'Fellow Lords, we treat Time as an enemy to be beaten, as the

Moon treated the Sun. Can we not learn from that lesson? In

battling against that which is the stronger, will we not merely

weaken ourselves? Look now through the eyes of Science. Time is a

force that can be measured, and if it can be measured it can be

understood. And if understood, it can be controlled. We should

not seek vainly to defeat Time, but should learn to ride it and

thus bend the world to our will.'

He spoke true, of that there was no doubt. Thenceforth, we turned

our energies and our minds to the study of Time; and the fruit of

our labours was the Moondial - such as this that you see before

you."

The old man reached out to the moondial and traced the line of

shadow that fell upon its scale. Then slowly he leant back and

stretched an arm heavenwards.

"Ha! There's little magik in this faint

white Moon. But in the days of which I speak the Moon was yet

red, though paler than it had been, and the magik was still there

for those that could feel it. By the light of this Moon, I can

tell what the time is. But by the light of the Red Moon, I could

tell the Time what it should be.

Thus we travelled through Time; and Past, Present and Future were

as one to us. We saw what had been, what is and what will be; and

if we saw ought that worked against magik, then we created what

should have been, what ought to be and what shall be. And the

empires of men began to crumble and fall, and magik came forth

from the darkness once more.

'Twas not easy, that re-writing of History, you must understand.

But we made progress - ha! - I should say we unmade Progress! And

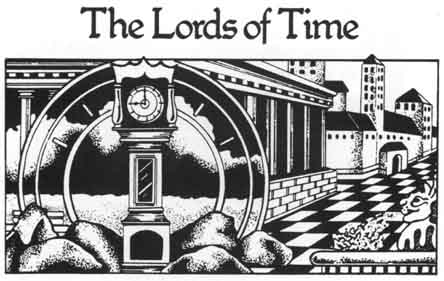

we called ourselves the Lords of Time and we were pleased with

our work, but the Timekeeper railed against us.

He would have no part of our interventions. While we other nine

had laboured over the making of the Moondial, the Timekeeper had

compiled a History of the World, and he foreswore any re-writing

of it. When he saw that his Present was changing constantly, and

realized what we were doing, he chafed and raged and sought to

stop us. But we were nine, and he was one.

We protected the secrets of the Moondial from him, and kept him

from our councils and our private towers. Yet so engrossed were

we in our labours that we failed to keep observation upon him. He

turned from his History, that which had become an account of what

might have been, and not of what was; then wrapped himself in a

shroud of secrecy and began to investigate Time for himself.

It took him time to master Time; but he did, and he built himself

a Timepiece - or did he build it? I have met many a paradox on my

travels through time, but this was the one above all. The

Timekeeper told me of it in latter days when we had made our

peace once more.

He discovered, as we had, that Time is a stream that winds

relentlessly through the landscape of life, carrying us on in its

current. 'Tis a deep, strong current. Fight it, and you may hold

still for a brief while but you can never swim upstream. Strive

to get ahead, and you may gain on it for a few short moments

before the current drags you down. Aye, there were those of us

that tried it and near perished in the attempt. But there is

another and better way to travel through time.

There are many places in the course of Time's passage where it

forms loops that bring Past, Present and Future close together.

If you can but reach the bank, and step out of Time, then can you

cross over to the Future or back to the Past. This is what he had

found. But having found this, he did not set out, as we had done,

to create a device that would allow him passage in all

directions. No, he could have done so, but our success in

reworking History to our design was nearing completion and he

felt the need for haste.

He built only the simplest device. One that would give him

transit across to the next loop of Time. It was a bold move, as

the device lacked the means of taking him back. If his plan had

failed, then he would have been stranded in a future that he

would have already reached by other means. That was a terrible

prospect. You must understand, the Timekeeper was not an easy

soul to spend time with. He could never have shared the rest of

Time with another of himself.

But his boldness was justified. He reached the future juncture,

handed himself the Timepiece that he would otherwise have had to

build, and returned to his Present. He knew, of course, that he

would have to hand the device back to his Past self when he

reached that future point with it, unless he created an

alternative future - and his scruples as a Historian would not

allow him to do that. Nevertheless, his move had won him the use

of his Timepiece during the time that would otherwise have been

spent in the making of it.

Ha! A brilliant ploy, yet with a fatal flaw. He, who lacked our

experience in these matters, did not know that any movement

through Time sends ripples across its surface. We others detected

them, saw that they had not been stirred by our activities and

traced them back to the Timekeeper. We could not see his

Timepiece, any more than we could see him, for it too was

enclosed in the shroud of secrecy; but we could sense his

presence - and his movements.

We followed him wherever he went, back and forth through Time.

And wherever he went, one of us would be there to forestall any

action. Yet in the end it was a close-run race, and he nearly had

the better of us, for his Timepiece had a greater power than

those we used. His was not a Moondial, to be used only when the

Moon rose in the Heavens. He had captured Time in a machine,

while we relied on the magik of the Red Moon, and the Red Moon

was fading.

But nine hounds and one stag, we wore him down, until he

abandoned his attempts to pervert that course of Time that we had

set. He retired to his tower and sat in solitary contemplation

for many a long day. We watched and waited, but he made no move

against us. At length, we approached and entered into his

citadel.

He had lain aside the shroud of secrecy and sat, as if waiting

for us, in his great oak chair at the head of a massive table

hewn from a single tree. His History lay open on the table before

him, a fresh-cut quill close at hand. As we came close he

gestured to us to take the chairs ranged along each side.

'Welcome, fellow Lords,' he said, 'I am honoured by your

presence. Please be seated. There is much about which we must

speak.'

He seemed philosophical, to have accepted his defeat, and said

that his interest then was only to correct the History that he

had written. He offered us a bargain, and exchange of secrets. He

would expose to us the mysteries of his Timepiece, if we would

but tell him what we had done, so that he may rewrite his book.

'But let us treat with the History first,' he said. 'That was my

great Work, and my first love and duty.'

Ha! He was ever the sly one! And we believed him.

We went through his History with him, pointed out the

interventions we had made, the inventions we had unmade, the

meetings we had arranged, the matings we had prevented - all in

Magik's favour. And at the end he asked us, each in turn, to say

what of all that we had done, we believed to be the thing of

greatest import. And we told him, and he wrote it all down.

'Now come, we said, 'Time it is for you to show us the working of

your Timepiece.'

'Indeed,' he replied, 'I shall do so.'

He stood and walked across towards the hearth. There beside it

stood a device in the shape of a grandfather clock, a beautifully

decorated and innocent seeming device. 'I set the Time so,' he

explained, opening the glass face and moving the hands. He closed

the face. and spoke again. 'Then begin its motion thus.'

Before we could stop him, he had opened the lower door and set

the pendulum swinging, and the clock disappeared. The Timekeeper

turned to us and smiled, and I knew why. For when he had reached

into the case of the clock he had dropped with a slip of paper. I

saw it clearly as it fell, and though it was for but a brief

moment, I can yet recall the words that were written upon it.

Into the cauldron you must throw an olive branch, make

friendship grow.

A dragon's wing, a sign of flight, An ivory tusk, a sign of

might.

Mix in the teardrop, a touch of sadness, and the evil eye, a sign

of badness.

Add a dinosaur egg, a sign of birth, with the jester's cap, a

symbol of mirth, plus the silicon chip, a vital invention, and

the golden buckle, a bone of contention.

If you do all this, before time runs out, a winner you'll be -

there is no doubt.

But take care when you find the lords, or you'll not gain your

just rewards, your quest will all have been in vain, and you will

have to start again.

Where has the Timepiece gone?' I asked, 'To whom did you

direct it?'

'It has gone I know not where, nor to whom,' he replied, 'I know

only that my fellow Lords will ever prevent me from using it, and

must hope that some adventurous human soul will take up the

challenge and restore the corruptions that you have made. Let

Time take care of itself.'

We slumped back into our chairs, angered that the Timepiece had

been spirited away from us, but not unduly troubled by the

thought that it might fall into the hands of Man. Ha! Was there

ever a human born that could match the Lords of Time?"

The old man had sat in silent contemplation at the ending of

that tale. He watched the shadow creep slowly around the Moondial

until the next hour was reached. then he began to speak once

more.

"Time had been locked in its course, and closed to us. And

the Red Moon that had been, was then dull and ashen white. Magik

was lost to the world, and lived on only in Baskalos.

To Baskalos we had repaired when our cloud castles fell from the

sky that noontide, when their fragile foundations of magik

collapsed with the fading of the Moon. Only seven of us were

there now, for three had perished with their towers. Living

amongst men, we took human names - Cazab, Golitsin, Hagelin,

Hollis, Skardon, Venona and Volkov.

We came together in Cazab's tower within the citv of Baskalos,

and there we turned our magiks to the rekindling of the Red Moon.

Ha! What vanity! As if we, whose powers stemmed from the light of

the Moon, could muster sufficient magik to set that orb a-glowing

once more. Yet we tried. For nine days we rehearsed our charms

and incantations, summoning up a lightning storm the like of

which had never before been seen on this Earth, nor ever will be

again. On the tenth night we set a vortex of wind spinning madly

up from the tower, forcing apart the thick black clouds above so

that the Moon was revealed directly over us, full but wan. We

called bolts of lightning down into that vortex and stood poised

with spears of magik ready to hurl them at the Moon, to carry the

tumultuous power up to it and thrust new fire into its ashen

body. A thousand bolts of lightning were drawn from the four

corners of the sky and coalesced into one solid pillar of

blinding, crackling blue-white power in that vortex..."

The old man paused trembling, his aged eyes aflame with the

memory of that moment. Then, abruptly, he gave a short rasping

sigh and shook his head.

"...and every jot of it went straight down into Cazab's

tower! The shock of it flung us into the air and left us strewn

throughout Baskalos. The tower was burst asunder, its stones

found later up to ten leagues beyond the city walls; and of Cazab

himself, for he it was that stood at the centre of the vortex, we

found nothing but a single smoking boot.

We six that remained came together in council some months later,

when our bodies and our powers had healed enough for us to move.

Venona had thought much about our problem during that time, as

had we all, and it was his suggestion that we should construct an

alternative focus and source of magik, that we should recreate

the Red Moon but smaller, in the form of a crystal. We were

loathe to abandon our intention to rekindle the Moon, but knew

that it was not possible at that time or place. Likewise we knew

that we must have some focus if magik was not to be dispersed and

lost for ever; and so Venona's idea was accepted.

In the city of Baskalos, in the castle of Xax, we caused to be

built a high tower. There within it we installed the Red Moon

Crystal, and on Mid-Winter's night, when the new Moon rose over

the distant hills, we joined our powers to infuse the Crystal

with the cold fires of magik. And a pure crimson light shone from

it and illuminated the city and the lands of the Kingdom of

Baskalos.

So Baskalos stood as an island of light and magik when all around

the world fell into the darkness of mechanics. The gardens of

Baskalos sparkled with colourful arrays of fragrant flowers

through all seasons of the year; the buildings were triumphs of

inspirational architecture; the people grew tall and healthy, and

lived long, happy and fruitful lives; and the Kings of Baskalos

were ever wise and noble rulers, their armies unconquerable yet

never sent forth in cruel conquest.

Peace and prosperity, music, magik and the carefree laughter of

children. What else could the heart desire?"

The old man looked across at me from under his hood, his lined

face enlivened by a wry smile. He raised a single eyebrow to echo

his question and I smiled and nodded in agreement.

Baskalos must have been Paradise on earth. Who could not have

been happy there?

"Know you, there were those of us that were bored near to

distraction before the end of the first century. Baskalos was a

small kingdom, its boundaries defined by the range of the Crystal

in the Tower of Xax. Those of us who eschewed domesticity and the

narrow delights of urban life were soon chafing for new

challenges and the view beyond distant horizons.

We travelled far through the realms of darkness, and the sights

that met our eyes filled us with deep sorrow. There was so much

pain and anguish, so much empty greed and degradation of the soul

in those lands of merchants and machines. We took our wisdom and

our lesser magiks with us, and did what we could to bring some

light into the dark places, but to little avail.

Kings would welcome and honour us, should we but put ourselves

and our powers into their service, so that they might tighten

their grip upon rebellious subjects, or extend their sway over

lesser lords. And there were those of us who would do just that,

in the vain hope that thus we might influence their rule for the

better. But if we sought to uplift their downtrodden subjects,

enslaved by armed might, or by the power of money or religions,

then would we be called Warlocks and Necromancers and hounded

from the lands.

Ah, if only the Red Moon shone still upon those unhappy realms.

Or if the King of Baskalos would extend his dominion. Surely the

lands beyond would be better places beneath his wise and just

rule. Mayhaps it would be possible to take the Red Moon Crystal

on perigrination through the outerlands. How much light would it

take to penetrate the darkness? These questions ran through my

mind constantly as I travelled in the world beyond Baskalos.

I returned one winter's day to the city determined to take magik

to the relief of the outer darkness, and went straightway to make

entreaty with the King that he should set forth on a conquest of

mercy at the first thaw of Spring. I was stopped by Skardon, ere

I reached the Palace.

'Volkov! At last!' he cried. 'Come at once for we have need of

your wisdom in our council.'

He explained to me breathlessly as we hurried through the snow

across the city to Skardon's tower. It seemed that he and Hollis

had essayed to build a new and greater Crystal so that magik

could be spread beyond the limits of Baskalos. I was surprised

and impressed, for they had ever been the ones to stay content

within the city while the rest of us had been driven far afield

by our desire to bring enlightenment to the world. So Hollis and

Skardon too had laboured in Magik's service, though in their own

way.

But why the haste? Does the time to illuminate this new crystal

fast approach? Or has magik been focussed within the crystal and

has Hollis subourned it for his own private gain?' I questioned

Skardon as we laboured through the thick drifts of snow.

'No, no!' he replied 'Tis not that. 'Tis... Why look, you can see

for yourself.'

We had rounded a corner and stood then in sight of Skardon's

tower. He pointed upwards, and I followed the line of his finger

and exclaimed in surprise. 'Why, Skardon! You have added a new

pinnacle to your tower.'

'Pinnacle! Forsooth! 'Tis no pinnacle. That which you see is the

new crystal; and look within.'

I cast my sight aloft and looked within. 'Twas not magik that was

contained within that crystal, but Hollis himself!

Skardon spread his hands in apology. 'I did not see that he was

standing within the hexagon as I made the final incantation,' he

explained. The crystal formed around him even as I stood and

watched. I have gathered together our fellow magicians and we are

now meeting to decide what to do.'

'Twas a difficult decision. Should we attempt to illuminate the

crystal with magik, even though Hollis was within? Could we

indeed succeed to do so without his contributions? Or should we

shatter the crystal to free him? And could we accomplish that

without shattering Hollis? We sat in deep thought in Skardon's

study, gathered round his great log fire, but could not settle

upon a course of action.

At length, I suggested that we bring Hollis down to join our

deliberations. He might have been able to signal to us his wishes

if he were there amongst us. They had been unable to bring the

crystal down by physical means - it was too cold and slippery to

be held, and in any case too large to pass through the stairwell

- but I was able to use my special facillities to transpose it

from the roof down to the study.

There it stood in front of the fire, sparkling and gleaming in

the light of the flickering flames, casting shafts of multi-hued

brightness throughout the room. Hollis stood statue-stiff within,

showing no sign of life, as much cut off from our deliberations

as he had been when on the tower's top. We repaired below to

Skardon's hall to dine and continue our discussions, and there,

over his well-laden board, we decided that the new crystal could

not be illuminated while Hollis stood within, but that it was a

thing of beauty and not to be destroyed. We therefore determined

that it should be transposed to the roof of Hollis's tower to

stand forever as a tribute to his memory.

'Twas at this moment that water began to drip through the ceiling

and Hollis, teeth chattering and soaked to the skin, appeared at

the door. The crystal had been formed of ice, and had melted in

front of the roaring fire in Skardon's study.

This experience did little to dampen Hollis' enthusiasm for the

project, and he and Skardon began to plan a second attempt at a

greater crystal. I was invited to add my skills, but having

looked through their designs and assessed the import of their

incantations, I had little faith in their eventual success.

Instead, I turned my attention back to the King of Baskalos and

sought to persuade him to extend his domains and to carry the Red

Moon Crystal into the new lands to spread the light of magik. But

he was old and set in his ways, and fearful of moving the Crystal

from the Tower of Xax. My fellow magicians too opposed the plan,

believing that the only hope for the future lay in cherishing

magik within the confines of Baskalos.

Ha! I was impatient for change and chafed beneath this

conservatism. I had done too little for too long, and knew that

the time for action had come. If the King of Baskalos would not

use the Crystal to bring the darkness under his rule, then would

I make it my own and set out to impose my own enlightened

dominion upon the world entire. And why not? There was no being

more fitted than I to take such a heavy burden.

But determining to take possession of the Crystal, and actually

laying my hands on it and removing it from the Moon Tower, were

matters of two different hues. The magik inherent in the Crystal

of Xax would resist any attempts to take it by means of lesser

magiks, and all magiks were lesser than that of the Crystal. Thus

I would be forced to resort to physical methods, and that

presented numerous difficulties.

In the three centuries or more since the creation of the Red Moon

Crystal, certain traditions and conventions had grown up around

it, as much in reverence as in defence of its powers. Foremost

amongst these was that we true Magicians should have contact with

it but once a year on Mid-Winter's Night, when a ceremony was

held to reconsecrate it to the Kingdom of Baskalos. This ceremony

also afforded us the opportunity to examine it for signs of aging

or imperfection, though I am pleased to say that such was its

quality that we never found any cause for concern.

Lesser magicians, the King and his lords, and all military men

were always denied access to the Crystal, for it was held that

its power would prove too great a temptation for them. The Castle

of Xax was therefore handed to the care of those two Guilds whose

members were believed to be the most trustworthy in respect of

the Crystal - the Blacksmiths and the Pastrycooks. An unlikely

co-operation, but one that worked well. They were all deeply

practical men, whose sole ambitions were in the perfection of

their crafts. The Blacksmiths provided physical strength and

force of arms, should such be necessary in defence of the Castle;

and the Pastrycooks contributed intelligence and sensitivity.

This Castle was situate in the midst of a small lake, and could

be reached only by a guarded causeway that ended in a drawbridge.

This latter was lowered but twice a day, to send produce to the

markets in the city, and to receive fresh supplies. Entry to the

Castle was therefore difficult, but this was only the first

stage. Any intruder would thence have to pass through the

inhabited rooms and workplaces to reach the inner courtyard where

stood the Moon Tower. Narrow windows let onto this courtyard, but

there was only a single door and the key to that hung on the belt

of the Chief Pastrycook.

These obstacles were problematic, but not insuperable. Was I not,

after all, a Magician of the highest degree? Had I not studied

men and all their crafts for millenia, and at close hand for the

past three hundred years? A simple disguise, a little subterfuge

and the judicious use of some lesser magiks would take me thus

far. The true difficulty lay beyond.

That locked door did not merely keep the inhabitants of the

castle out of the courtyard; it equally kept the inhabitants of

the courtyard out of the castle. Seven gryphons lived there, ever

restless and hungry, patrolling constantly and sleeping never.

They, and the four great falcons that nested above, were the

incorruptible guardians of the Moon Tower. Infused with magik

themselves, and living always so close to the Crystal, they could

resist all my incantations, withstand all my potions, and sense

my nature and purposes through the deepest disguise. How then to

pass the gryphons?

Though I pondered long and hard within my tower, the answer

came never to my mind. And then, one autumn evening, eating

pastries by my fire, I had an inspiration.

The following morn, I went straight to the market, lighted on a

pastrycook that stood momentarily apart from the rest, and in a

trice had magiked him to a distant city, where I knew his skills

would be in great demand; donned his shape and his memories, and

took his place. That eventide I returned to the Castle of Xax

with his fellow cooks and took up residence there, the better to

learn its secrets.

They were a happy band of brothers, those men of Xax, delighting

in their crafts and comradeship. And it was a pleasant life, one

I could have endured for many years. I had a cell close by the

inner courtyard, and through its slit window I kept surveillance

upon the gryphons. They sensed my closeness, of that I am sure,

and for some while the men of the castle wondered what made the

beasts so restless. But men will ever seek to explain the unknown

as simply as they can, and so the cooks and smiths decided that

it was merely the onset of winter that disturbed the gryphons.

My opportunity came at last, as I should have realized it would,

on Mid-Winter's Day. That night was to be held the ceremony of

reconsecration, therefore the gryphons and falcons must be

removed from the courtyard so that the magicians and the King

could have access to the Moon Tower. That day there was no

delivery to the market place, but the entire morning's bake of

sweetmeats and delicate pastries was laid out on great tables

within a high chamber close by the door to the inner courtyard.

When all was ready, the cooks retired to the perimeter of the

antechamber beyond and watched as the Chief Pastrycook walked

resolutely through and unlocked the courtyard door.

Then he swung open the doors, and stood aside, armed only with

his strength of purpose and his rolling pin, and watched as those

terrifying beasts swarmed in for their yearly feast. As they set

upon the food, he closed the chamber doors behind them and locked

them fast. The way through the antechamber to the courtyard and

thence to the Tower lay open!

A number of the cooks were then detailed to go out into the

courtyard and make it clean for the passage of the King that

night. I went with them, and made myself busy while seeking for

an opportunity to approach the Tower without being seen. A besom

broom in my hand, I swept a circuitous path towards the Tower

door, then, when no eyes were upon me, I slipped the catch and

eased myself inside.

There were no rooms in that tower save the one at the top where

the Crystal lay. Below that was nought but the stone stairway

that spiralled upwards, steep and narrow. It was dark in there,

with only the faintest glimmer of red light filtering down from

on high. I walked up steadily, keeping close to the tower wall,

tense with anticipation at being so near to my prize.

Yet even then I had doubts. Once, twice, I stopped and almost

turned back down. Not that I feared discovery, or the wrath of

men or of my fellow Magicians; but that deep in my heart I could

not be sure that I could resist the awesome temptations of the

power that the Crystal held. I shook off mv doubts and pressed on

upwards. The light grew brighter and the thrill of magik grew

ever stronger as I approached the top, until I was at last there!

I stood on the topmost stair, almost blinded by the light of the

Red Moon, now but two steps away, when I heard a sudden rush in

the air. Hagelin, dressed in blacksmith's garb, came in through

the window and swept up the Crystal into his arms. I gasped in

surprise. He turned and saw me and laughed. 'You look tired,

Volkov!' he cried, 'Did no-one tell you that flying is easier?'

With that he launched himself through the window and was gone,

and the Crystal with him. I had been but two paces from

possession of it!

Where now was that wonderful Crystal of the Red Moon?"

A small cloud drifted in front of the Moon, throwing the

moon-dial into darkness. The old man gestured towards it and

spoke wryly. "See. I am lost in Time without the Moon. Was

it not ever thus!"

His huddled figure seemed to have become even more bowed and

fragile than it had been when I had first encountered him, yet

his voice was still firm and strong as he started upon his third

tale.

"Time takes its toll on all who live within it. And even we

who were there at its beginning. must reach an end. Magik too

makes its adherents pay a price.

When it became known that one of our number had stolen the Red

Moon Crystal, the people of Baskalos grew suspicious of all the

Elder Magicians. And in the absence of the Crystal, there was

little to hold us to that place. Therefore, our company departed

in our several ways; Skardon and Hollis made off for the Far

North to experiment further with their crystals of ice; Venona

set out for the East; and Golitsin and I turned our faces to the

West, and thence travelled singly. And Hagelin? I heard no more

of him, and must judge that he was lost when the Moon Crystal was

found - as it was some time after.

We never again gathered in Baskalos. even after the Crystal was

restored to the safekeeping of that city. Nor shall we all meet

again anywhere in this world.

I yet had much strength and vigour, and though distance from the

Moon Crystal robbed me off my greater powers, still I possessed

my wisdom and a whole host of lesser magiks. These qualities were

sufficient, in those days of ignorance and barbarism, to ensure

my leadership of men wherever I went. I amused myself for many

centuries in the pursuit of architecture, erecting great

monuments of stone, knowing full well that lesser mortals would

look upon them afterwards and marvel how they came to be built.

Even now I smile to myself as I walk through the world and see

them wondering at my pyramids and temples, saying 'How could Men

make such things?' Ha! Men! They could never equal my

constructions for all their technology.

Meantime, while I made my entertainment in the realms of

darkness, a Golden Age had been born in Baskalos. When the Moon

Crystal was recovered, it was given to the safekeeping of the

Guild of Scholars and Wizards, and they had decreed that the one

of their number who was most wise and least worldly should take

responsibility as the guardian of the Crystal. The guild always

did well in its choosing, and over the years a long succession of

guardians had cherished and nurtured the Crystal, so that it

gained steadily in power, until, at the time of which I am

speaking, its light shone out far beyond the limits of the

Kingdom of Baskalos.

Then Satyr, that had been the guardian, passed away, and the time

was come for another election, and they chose from their number

the one who was called Myglar. He had travelled far, and had

learnt much wisdom and magik upon his travels. I had myself

initiated him in many of those ancient mysteries that had been

lost to Baskalos, for he had sojourned with me for some time in

the outerlands of the West. On his return to the city, he had

freely shared his new-found lore with his fellow guildsmen and by

this action had won much gratitude.

Myglar had protested against his election, saying how unworthy he

was of the honour, and how little he could be trusted, and how

greatly he feared the temptation of power. His electors had

smiled when they heard this, and congratulated themselves that

the choice was good, for surely only he who knew his limits and

his weaknesses could rise above them. And Myglar had smiled

secretly to himself as he bowed to their urgings and took up the

guardianship of the Crystal, for he had known that his

protestations would but make his position the stronger.

Myglar's election came as no surprise to me. Had I not shared my

life and my lodgings with him? Had I not watched as he politely

devoured my secrets, and seen the way that, with obvious

self-effacement, he could thrust himself to the fore? Were not

his gifts so freely given that the receiver stood forever in his

debt? Aye, Myglar was ever ambitious for power, though he hid it

well from mortal eyes. But then, mayhaps it were a good thing

that the guardian of the Crystal should be ambitious, for would

he not then be more assiduous in its care, that its magik might

grow and his power with it?

He must surely have served his office well at first, for when I

moved to Aranstan, beyond the mountains that stood to the west of

Baskalos, I felt the touch of the Crystal that had never reached

so far ere then. Indeed, I began to make use of that power for

the first time in many years, and set upon the greatest and most

elaborate design that I had ever attempted, a magnificent,

soaring bridge of stone that would arch across a vast chasm.

That chasm was so wide and so deep that it could not be spanned

with a temporary framework of wood such as we would normally use,

and without the closeness of the Crystal even my powers would

have been unequal to the task. But as it was, I was able to

create a rainbow of moonlight of such strength and solidity, that

the stone arch of the bridge could be assembled upon it.

We had almost completed the task - indeed, the keystone stood

ready at one side of the chasm, waiting to be carried out to the

centre - when the rainbow trembled for one brief moment. And in

that moment all was lost. The stones of the bridge fell tumbling

down, down into the depths of that great chasm, falling for an

eternity before at last they reached the river far below. So far

below that the sounds of their impact never reached us.

I knew then that things fared ill with the Red Moon Crystal. and

set forth straightway for Baskalos. It was a long journey, for I

had been on the wrong side of the chasm when the rainbow gave

way, and, though it had re-formed I would no longer trust it to

hold my weight. Thus must I walk the length of Aranstan before I

could cross the river and turn my face towards Baskalos. By then,

winter had taken its grip upon the land and the mountain range

that stood across my path was well nigh impassible.

Mayhaps I should have tried the crossing despite the deep snow. I

had felt the flickerings and falterings of the Crystal's magik

and knew that time was short, but that very failing held me back.

For as the magik of the Red Moon weakened, so did mine and to

have attempted the mountain crossing then would have meant almost

certain death.

Through the long winter, the longest and hardest in all memories,

I kicked my heels restlessly in the village of Langley in the

foothills of the range. At last, when spring had brought forth a

rush of bright flowers and the streams were in full spate with

the melting of snow on the mountains, I made ready to start the

final stage of my journey. It was then that I felt the presence

of another Elder Magician not far off. I sent out my thoughts to

him and sensed his response.

Again I waited, fretful at the delay but eager for the company

and assistance of a fellow on a difficult and dangerous journey

towards I knew not what. On the second day I spotted Golitsin

hurrying up the valley towards the inn where I had made my

lodgings, and soon we embraced like long-lost brothers.

When did you feel the faltering of the Magik?' I asked, for I

knew it was that which had brought him there.

I was in battle,' he replied. 'I had gone to the assistance of a

weak but goodly lord who faced a mighty foe. The enemy had fallen

upon us in great numbers and the fight had gone badly against us.

I had rallied our forces round me for one last valiant stand when

of a sudden I felt a fracturing in my Moonshield...'

'And all was lost!' I broke in upon him.

'Nay.' he said with a wry smile. 'The shield disintegrated with

such outward force that the enemy was laid flat and we won a

famous victory! But the shield was no more, and I knew that I

must return yonder to Baskalos. And you,' he continued, 'what

were you doing when the Crystal first failed?'

'Let us say that I was playing bridge and lost a trick,' I

replied. and he laughed for he had heard, as I knew he would

have, of my calamity at the chasm.

We debated much on the fate of the Crystal during out journey

over the mountain range. I held that Myglar's successor had been

badly chosen, or perhaps the scholarship of the Guild had decayed

so far that there were none fit for the stewardship of the

Crystal. For Myglar must have been dead by then. He would have

been long past the span of human years, and it was known that the

Crystal took its toll of its guardians. Golitsin, who had spent

most of the previous century on military pursuits, was inclined

to the belief that Baskalos had fallen under barbarian rule, and

that the Crystal itself was. under attack.

We were both wrong, as we discovered when we entered the realm of

Baskalos. The kingdom yet enjoyed peace and prosperity, though

even here the falterings of magik could be seen. The early crops

did not have the lustre and fullness of the past, and I saw the

first stirrings of diseases that, though common in the

outerlands, had never troubled the people of Baskalos.

And Myglar was yet alive! We heard thus from the peasants and

could scarce believe it, yet 'twas true enough. On our second day

in Baskalos, we were met on the road by a body of Myglar's guards

and courtiers.

'O wise ones of the Elder Days!' their leader greeted us. 'My

Lord Myglar bids you welcome to Baskalos in its time of need. and

entreats you to allow us to escort you to his castle.'

'Fair words, but I trust them not,' muttered Golitsin as we

mounted the horses that they had brought for us. 'Myglar is yet

alive. That can only mean that he has been drawing life from the

Crystal itself.'

'Aye, he was ever the smooth one,' I agreed. 'But he is cunning.

He will not hope to hide his corruption from us. This is no guard

of honour that surrounds us, this... Ha! Did you sense it?' There

had been a shimmering in the veil of magik that lay over

Baskalos, and I had felt a sudden chill deep within my innermost

self.

Golitsin nodded, then started as the shimmering came again.

Myglar was draining the Crystal's power while his vassals delayed

us on the road.

'We must make haste,' said Golitsin urgently. 'But how to rid

ourselves of these guards?'

'By boldness,' I replied, then cried out loud, 'Ho! I hear you

master summoning us! Ride hard, men of Myglar.' I spurred my

horse on savagely, Golitsin at my side.

The guards knew not what to do. They could not attack us on the

open road, but must strive to keep up with us and hope to

forstall us ere we reached Xax. But this they could not do.

Golitsin and I had the form of men, but not the substance. We

rode our steeds as light as thistledown, while the guards weighed

heavy on theirs. By the time we passed through the city gates, we

were nigh on half a league ahead. The city guards too were taken

unawares by our sudden rush. They called to us to stop, but we

were long gone by then. On we galloped to the castle, cross the

drawbridge and through to inner chambers.

The doors were locked that led to the courtyard wherein stood the

tower of the Moon Crystal. Golitsin tried a spell of unlocking,

but the door had been proofed against that. I called down a

thunderbolt to blast our way through, yet in vain. Myglar had

placed a magik on that door that resisted all our efforts. In

desperation. we took the form of owls, that we might fly through

the windows and thence to the top of the tower. 'Twas desperation,

for as owls our own powers would be much reduced. Our hope was to

gain access to the tower room and return to human form before

Myglar could intervene.

'Twould appear that Myglar had found some way to view the future,

for certainly he seemed to anticipate our every move. As we rose

into the courtyard together, we were met by a massive black

falcon, swooping down upon us. We dodged and dived, but that

great bird, for all its size, was every bit as agile as us. We

parted, and flew either side of the tower. The falcon, closer to

Golitsin than to me and smelling blood, rushed after my

companion. Behind and below I heard a shrill cry and a flurry of

feathers, then great wings began to beat the air in pursuit of

me.

With moments to spare, I reached the sanctuary of the narrow

windows of the tower room, flew in and alighted in human form

once more. The Crystal was yet there on its pedestal, and for an

instant I was lost in wonderment of it. For all it was pale and

wan, it yet had such beauty, such symmetry; its light, though

sadly dimmed, remained so pure and clear. How well it had

fulfilled its task in those long centuries since the setting of

the Red Moon!

That moment of reverence was my undoing. Myglar hopped down from

the windowsill and stepped between me and the Crystal.

'Meddling Magician!' he hissed. 'What ill wind brought you back

to take my Crystal from me?'

'Myglar, that Crystal belongs not to you, but to Magik itself. No

man can ever own it. Its power is too great to be borne by one. I

reasoned with him to gain time while I felt for the limits of his

magik with questing fingers of thought.

'Seventy years I have tended this Crystal,' he replied, raising a

cloaked arm to encompass it. 'I know it well. It is in my power.

Mine alone!'

I launched shackles and chains of moonsilver at his hands and

feet to hold him still. But alas, as they touched him, they

turned into wisps of moonlight and disappeared. Myglar laughed,

and with a flick of his fingers threw up a wall of glass between

us. I made it into a curtain, pulled it aside and set to rush

upon him. He grasped the Crystal and held it aloft. poised to

dash it against the floor.

'Stand back!' he cried, 'Or you shall be responsible for its

destruction!'

Ah! The Crystal of the Red Moon! Would it be better broken into

pieces than left whole in the power of that madman? I knew not,

and while I hesitated, Myglar made the decision for me. He

enfolded the Crystal within his cloak and as its red light

disappeared, so did he.

Oh, the pride and the folly of it! The Crystal would do Myglar no

good. True, it would stave off death for as long as he clung to

it, but what life would he have? Such selfish ownership of such

terrible power must lead him fast to madness. He would pay the

price, the price of magik."

The old man sighed heavily and was silent for some time before

speaking again.

"The Crystal was at length rescued from Myglar's grip, and

restored to Baskalos, but magik was never the same in after

years. The end of the Age had come. and true magik was

disappearing from this world.

Now there is but little, and that only when the full Moon shines

bright and time can be measured on a moondial once more."

I gazed down at the moondial that lay between us. The setting

Moon had pushed the shadow of the gnomon to the very end of the

scale, and even as I looked a new shadow, cast by the first rays

of the rising sun, fell starkly across the face.

Then the moondial was gone, and the old man with it.