Scanned in by Jeremy Smith

Written by

Dale and Shelley McLoughlin

Published in Great Britain 1985

(c) Mikrogen

Unit 15, Western Centre, Bracknell, Berkshire.

0xxx 4xxxxx

Reproduced and printed by

Lucas Graphics Ltd.

14 Easthampstead Road, Bracknell, Berkshire.

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

Athron took the rusty old spade in his hand and began the arduous task he had set himself for that day. It was hard work and he could not truthfully say that he enjoyed it, but it had to be done. When finished he knew that he would feel the warm glow of self satisfaction that accompanies any job well done, but for now he would have to put his mind into the effort and forget any thoughts of what he might have been doing otherwise. It was not to be a large hole anyway.

The spade moved swiftly in his powerful hands, biting great chunks from the soft earth and piling the soil neatly at his side. Before long he had reached the harder clay below and his pace began to slow a little. He mopped the sweat from his brow and decided to rest.

"If I were a troll," he thought, "I could have this done in half the time! But then the sun would have turned me to stone long since!" He laughed and sat down to take a sip from his water jar. There were no trolls in real life, but it was an amusing thought.

As he sat resting, with his face turned away from the hot sun, he saw something glinting in the earth beneath his feet. He would not have thought much of it but the sun was bright and the glinting looked to him like a precious stone buried amidst the mud and dirt. With his bare fingers he scraped away the brown loam which all but covered the strange object.

To Athron's disappointment it was not a precious stone, but something larger, like a box or a casket. He lifted it from the ground and brushed the moist dirt from its top. It was not large, perhaps the size of his two hands cupped together, but heavy for such smallness. On one side there was a locked fastening with a tiny key hole that was all but blocked with dirt.

The young farmer examined his find carefully. The top and bottom were the same, made of leather perhaps and decorated with signs and writing that he could not understand, even though he could read the common tongue well enough. He could not unfasten the lock but the two halves parted just enough to see a little of what was inside.

It was not a box, it was a book.

Athron finished his digging well before sunset and returned home with the book tucked inside his tunic. His pretty wife greeted him at the farmhouse door and he went inside for his well earned supper.

The young farmer was a tall, muscular man with a dark skin and fair, sun bleached hair. Innosar, his wife, was shorter and lighter in complexion and her normally slim figure was rounded by the child that she bore within. Both of them had lived all their lives in this southern part of Oronfal. Athron was the youngest in a long descent of farmers, and Innosar the daughter of a cattle merchant.

"Look what I found," Athron said excitedly as he sat at the kitchen table. He placed the book beside his plate and poked at it with his knife.

"It looks like a diary," his wife replied, "who's is it?"

"Mine now, if no one else will claim it," he said, "but what shall I do with it?"

Innosar made no reply, but when her husband had finished eating he set about

the lock with his knife, prising and prodding, but all to no avail. The book was firmly shut and resisted all attempts to gain entry. It was almost as if some magical force protected it since the binding was not strong enough on its own.

The next day Athron set off to market with a wagon load of potatoes, four young puppies and a strange book, all to sell for the right price.

The small farm was situated near the smith town of Morath. This old settlement had stood for years on the flat plain south of the Redmier forest. It was walled like a fortress, though nobody really knew why, with a tower at each corner of its square perimeter. At the centre of the town stood the tall Morath Tower, which was always topped by the banner of Oronfal. The tattered old flag would flap wildly in the slightest breeze, much to the amusement of the local inhabitants.

The land close to the town was fertile and flat, ideal for the growing of crops and the raising of lesser animals, like cattle and sheep. A pleasant green landscape spread for miles around, broken only in autumn by the ripening crops, and sometimes in winter by a light snowfall. Every year brought a bounteous harvest of wheat, barley, corn and root crops and the Morath markets were always filled with the bustle of buying and selling.

Yet it was not for its market that Morath was famous throughout Oronfal. The town was named after the blacksmiths who plied their trade within its wall. They were the most skilled men in all the land, and farmers would travel from every corner of Oronfal for a Morath plough or scythe. Nowhere else could such fine blades be found, nor the men capable of producing them.

It was only a few miles from Athron's farm to Morath but the old oxen that pulled his cart travelled at their own leisurely pace and the journey took over two hours. When he finally arrived the market was busy already and Athron set up to sell his wares in a corner of the old trading square, beneath the Tower. Business was good and the potatoes were sold in no time at all, mostly by the sack load but sometimes in larger lots. Ml but one of the puppies was gone and the other was promised to an old friend in return for some seed in a week or two.

only the old book had gathered no interest, although Athron was not really surprised. He had shown it to some of the passers by. Some were curious and others not. Some seemed scared of it, though Athron could think of no reason to be. Still, there was something about the book which made even him unsure. It seemed to burn a hole where it lay in his tunic, as if it did not wish to remain there. Yet Athron himself was almost overcome by curiosity, desperately wanting to know what was inside that old binding.

At the end of the day he left his oxen tied to a watering trough and joined his friends for a jar of ale and an hour of gossip at 'The Market Inn'. When he arrived he found a seat with his old comrades who poured him a drink and bade him stay. At first they spoke of the weather, the market and business. Most of them were farmers, one was a smith and another a shop keeper, but all had known each other for many years and had shared in each others' lives.

At last Athron produced the book. He wondered what they would think of it. Perhaps one of them would know it, or of it.

"I've no time for books," said one.

"Does it have a story," said another.

They all showed little interest and Athron mentioned it no more, but all the while he was drinking and making merry with his friends he had just one thing on his mind. Only a Satyr sitting alone nearby seemed to prick up his ears with interest, but he said nothing to the men, and Athron was too polite to trouble one of the Amarin race with so trivial a matter.

Several days passed by without much ado. Athron went on with his work as usual and life seemed much the same as before. The book had lost some of its hold over him and he was not so troubled by it as he had been at first.

Then one evening he returned home at the end of a long day to find Innosar waiting for him, almost dancing with excitement.

"A Satyr, a Satyr," she said, almost unable to speak, "he came here. He wanted you!" Athron could not believe his ears. He knew none of the Amarin and he had seen only a few. They seldom troubled themselves with the lives of men; they had no reason to. And Athron was not concerned with the Amarin either.

"And what did he want, this Satyr?" he asked, not really knowing whether to believe his wife.

"He brought you this."

The woman held out something small between her finger and thumb. Athron could not see what it was until she dropped it into the palm of his outstretched hand. It was a key, a small silver key that shone in the setting sunlight and seemed to dazzle with what little luminance there was.

Then Athron remembered the 'The Market Inn', and the Satyr who had sat nearby, and the book. Yes the book. It had a small keyhole set into the leather fastening at its side. A keyhole just right for a small silver key.

Athron rushed to the chest where the book now sat, still a little dirty, but just as mysterious as when he had dug it from the ground only a few days before. The key fitted its tiny lock but would not turn. Again and again the young man twisted the small sliver of bright metal. He turned it this way and that, sometimes using all his Strength, but it would not release the lock.

At last, in frustration, Athron threw the book on the floor, cursing and swearing in his temper.

The old tome landed at Innosar's feet. For a moment she looked down at it in silence. Then she stooped to pick it up. In her innocence she tried to accomplish what strength and force had failed to achieve.

The silver key turned quietly between the young girl's fingers and the book fell Open at its first page. Then Athron saw what his wife had done and he snatched the prize from her hands, knocking her backwards with the force of his swift movement.

Innosar lay on the floor and looked up at her husband. He seemed to have changed. Something seemed to take hold of him and lead him away from the path of goodness that he had followed for all his life, taking him instead into a world of evil that had never been known before in this world.

Athron hesitated for a moment and then began to read.

But what he read was not good, and as he read it his world began to change around him. Suddenly, where there had been happiness there was now suffering, and where there had been kindness there was hate. For in reading those pages Athron released all that was evil upon his world. Hatred, Greed, Jealousy, Pride and Anger were set loose to roam free, and the once idyllic land was turned against its inhabitants. Man was turned against man, and all the beasts and races of the world were set in conflict with each other.

And when he finished reading, the words of the book slowly dissolved away, leaving only the empty pages from which they had come. Yet one word was left behind and Athron read this aloud, "Hope" it said, and that was all that remained in a sea of emptiness.

The Royal Palace of King Theltiem stood just a few miles from the river Milfair. To the south west lay the bridge that joined the island of Oslar to the eastern bank of that great waterway. The palace itself, called Oronoman by its people, was a grand and elaborate building built of great white stones which had been hauled across the river from the Storm Land to the west. That had been an astounding feat of strength and courage, but had taken place many hundreds of years in the past and was now little more than a legend. Only the building itself remained as testimony to those who had laboured in its construction.

Oronoman was the royal seat of the rulers of the land of Oronfal. Theltiem could trace his line back through the ages, even to the time before his palace had been built. In those far gone days mankind had been in his infancy and the other mortal races had ruled the world with a greater potency than now. They were still respected of course, but it was said that their time was gone, that they no longer held the awe of men and could demand no more respect than a man of equal standing.

But even King Theltiem was not so young now. Though his name meant Brave Heart, his people now called him Emasar, or White Hair. It was not said discourteously, but used as an endearment since he was loved and respected by his people and under his rule they had all prospered and been happy. He had lived in this world for over three score years, and ruled the kingdom for most of those. He was known for his fair speech and good humour, but in recent years age and ill health had taken their toll and left his body withered and bent.

His only child, a son and heir, was Mithulin, Treasure Seeker. He was a tall, strong lad of around twenty years, who was also liked by the people and respected for his views, despite his age. He had inherited much of his father's character and would often sit at the King's right and counsel him when required. Sometimes he would even offer advice without being called upon.

Theltiem thought that it was good to give Mithulin kingly duties before his time. Yet he did not overburden him with them. Instead he took careful measure of all his son's duties and tried to guide him through a happy youth towards a fruitful life.

One day Theltiem was at his court, giving judgement on a case of dispute, and Mithulin sat by his side.

The King spoke authoritatively but not harshly. "Then Fillen, you say that the fence is upon your land."

"It is, Your Majesty. The land is mine and was my father's before me."

"And can you prove it to be so?" Mithulin enquired.

"I can," came the reply and the farmer began to produce a paper from his jacket; a small deed tied with a ribbon and sealed with red wax. But he had no opportunity to read it to the court.

Suddenly a great booming sound was heard outside the palace, like a roll of thunder that can find no place to rest, but louder and mightier than any that had been heard before. Its noise was deafening even to those inside the throne room of Oronoman. It made the stone of the palace shake and the bells in the tower ring from its vibration.

But when the light was gone there came the darkness and the wind. It blew trees from their roots and people from the ground and in the darkness you could see nothing beyond your own hand. The air was heavy with a stench like rotting flesh which made the people retch and vomit.

Then suddenly, as it had come, the horror vanished and everything appeared peaceful as before. But life could never be the same again for any man present, for King and Heir, for farmer or servant, because the powers of evil had been set loose upon the world and had taken hold, however slightly, in every mind that lived and breathed. It was the beginning of a new age.

At the edge of the Deep Pool the old washer woman sat pounding her clothes against a smooth rock and singing as if no care could ever wrinkle her brow. Her song was one of simplicity and innocence; she had been taught it as a child, and had since sung it to her own children and now to her grandchildren.

Awaiting by the water's edge, I saw a maiden sitting there.

And as she washed the clothes she had,

Gentleman came passing by.

'Good day' he said, and sat him down.

Beside the girl who smiled at him.

And as she rinsed the clothes she had,

He looked at her, so young and slim.

The music rang out sweet and clear, but the song was not finished that day.

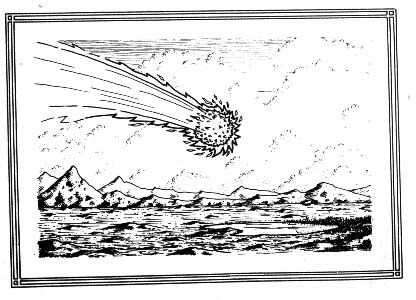

Suddenly a great ball of fire appeared in the sky, travelling at an enormous speed and unlike anything the old woman had seen in all her many years. It flew like the swiftest bird, yet higher than any beast could hope to reach. It went like a shooting star, with a tail reaching out far behind, but it was bigger than any comet yet seen from this land.

Then it ceased its movement across the sky, turning downwards now to head straight towards the ground. It looked to the old woman as if she would perish as the ball came closer, but instead it went towards the pool and plunged at full pelt into the cold water.

A great torrent rose from the surface as the meteor went down and the rain that fell from it was hot. It blistered the woman's skin and made her cry out from the pain. Fortunately it did not last long and was followed only by a yellow mist that stank venomously and hung in the air for hours afterwards.

The old woman did not wait to see what might happen now, and she fled home screaming. But her life was changed, and so was that of her children, and of her grandchildren.

In the Palace of Glass, Holdin Belanshar, Captain of the guard, reviewed his men as they paraded in the setting sunlight. This was part of the army of Falforn, the Storm Land, though it was a small force and had fought no battles and won no wars. It was an army in name only and performed just the ceremonial duties of the Queen, since there were no disputes with neighbouring kingdoms or uprisings of the populace to control.

Even so, they were a proud band, and skilled in the arts of war, though there had never been a need to employ those skills.

They paraded to show their prowess at drilling, to display their shining weapons and polished gear. They marched up and down, wheeling this way and that, halting and saluting as they went. Holdin was pleased with them all, and proud, and happy.

Then, as they stood silhouetted against the reddening sky, something entered each of their hearts. They all felt a yearning that they had never felt before, and a desire came over them which each had perhaps stifled for a lifetime, not wanting to admit its existence. Or perhaps they had just been unaware of its true meaning. Suddenly their minds changed and a force of evil took control of them. Each soldier produced his sword with only one word upon his mind.

"Kill!" they all shouted, almost in unison.

Their swords worked with swift and deadly accuracy and when the bloody massacre was over only one stood alive, bewildered and regretful.

Holdin Belanshar stepped over the bodies of his troops and fled from the Palace, afraid for his life and not understanding what had happened to him and his comrades.

The Dwarf Hall of Rimersel, or Lofty Dome, had stood at the southern boundary of the Storm Land for over a thousand years. It was a great lofty building topped with a giant dome, from which it received its name. It was said that the dwarves had built it in mockery of the domed heavens, and as a way of strengthening their alliance with the rock of the land. It also showed a defiance of the other races which had arrived at the same time as the dwarves but had since been more prosperous. They had been endowed with powerful minds and more intricate skills of craft than the dwarves and had quickly come to dominate the land on both sides of the river.

To the south the tall mountain range of Orosema spread for miles, its snow capped peaks ending only at its western edge in the impenetrable desert of Kora, and to the east at the River Milfair. Dwarf legend told of how the first of their race had come from below those very mounts and had spread northwards across the plains and hills, eventually crossing the river itself to settle in all parts of the land. That had been many thousands of years ago and they had since retreated towards the place of their making. Most dwarves were now to be found living close to Rimersel.

Yet still the mountains were impassable to any living being, either dwarf or man. The peaks reached for miles into the sky and though the lands about were hot and dry the tops of the mountains were always snow covered and cold.

The dwarves did not care much for their human neighbours, who tended to live further to the north. Still, they were friendly enough, trading when necessary but otherwise keeping themselves to themselves. It was a way of life which suited this sometimes secretive race and though they would treat a human visitor with kindness, any dwarf would try his best to hasten a man's departure.

Men generally considered the dwarves to be rather simple folk, though this was not really true, being based more on a lack of understanding for their way of life than actual knowledge. The dwarves were stout hearted, trustworthy and strong, and the length of their memories was matched only by the length of their beards. However, it paid to remain on good terms since an angry dwarf would be foe indeed, and despite their lowly stature each could inflict a blow worthy of two or three men.

Sharmek Helm Head was leader of the dwarves living in the domed palace of Rirnersel. It was he who decided their policy and politics. He controlled their production and consumption, and he was commander-in-chief of their own army.

The army had been only recently formed, since it was decided that the increasing numbers of men and other creatures living in Falforn might pose a threat to the continued existence of the dwarves at Rimersel. Whether this was true could not be confirmed, but there had been rumours of dwarves being persecuted at the court of Queen Rolquin. It was a risk that Sharmek had decided could not be taken and so a strong army was recruited and armed, just in case.

The formation of the army, and the general unrest among the dwarves, was an indication of how life had changed in recent times. Their society had become corrupt. Dwarves were caught stealing and vandalising, something which would not have been dreamed of in the past. The punishments had been strict too and resulted in dwarf killing dwarf for the first time in all their history. But the times were changing at an alarming rate and the tide of progress seemed to have turned back to give way to a ruthless, violent age.

Yet this had not been a gradual process. To an outsider it would have seemed obvious that dramatic changes had taken place almost overnight, but to the dwarves themselves there were no detectable differences in their lives.

It was early one morning when Sharmek sat with his captains. They met every morning to discuss the coming day and plan their manoeuvres.

He was a rough and crude dwarf, even when compared to his companions. Yet he had become even harder since the day Athron had released chaos upon the world. His temper was now quicker than ever and no-one dared to countermand his order or question his decision.

"It is some time since we had word from Oslar," Sharmek began, his gruff voice echoing around the council chamber of Rimersel.

"It is," replied Kirkmere, picking the remains of his breakfast from his beard. "I have a fear that the news will not be good when it does come. There are more rumours about. I have heard this very morning that the men of Oronfal have taken Ilis Clair for their own and threaten to carry her to Hail-an-Hes. And the Amarin have taken arms and are moving west from Harvena."

Some of the others nodded in agreement and a discontented mumbling circulated around the oval table, ending only when Sharmek rose to his feet and hammered against the wooden board.

"Then we must act," Sharmek said, even more sternly. "We cannot afford to waste time. The army of Queen Rolquin can move faster than us and it would be folly to ignore these rumours. No doubt she will take heed of them and act to protect her interests. In that case we must send an army north, to show our strength and resolve. And to teach the men a lesson they will not forget."

"But what if the rumours are not true?" Kirkmere asked.

"Then we are a dwarf band on a journey to see Ilis Clair, to seek her judgement and ask for her blessing in the future."

Sharmek looked around him with a malicious glint in his eye. None of the captains spoke again and with that they all departed to muster their divisions and to prepare for the march ahead.

To the dwarves of Sharmek's army the news came as a relief. Many of them had been spoiling for a fight since their first day at arms and only now did it appear that there might be some action. Just a few were a little apprehensive, but it was not within a dwarf's character to show any fear or trepidation. It was a foot soldiers lot to die for his comrades and his leaders, if need be, and none of the Rimersel folk would dare to break the oath of allegiance which each had sworn:

"For glory, for good, for dwarf folk, for life, In battle, in service, to give and to die."

It took very little time for the army to prepare. Every soldier had kept his weapons polished and sharp. And like the rock from which he had come, a dwarf could live on little food and water.

Nearly ten thousand set forth from Rimersel that day. There were so many that it was an hour between the first and last to depart. They all travelled on foot, not at speed but resolutely setting one pace after the next, never seeming to tire and never slowing. They carried all the weapons of war that could be mustered. Some brought only the scythes that they used in the fields, though that was weapon enough in such strong hands, whilst others carried great two handed battle axes forged by the most skilled smiths in all the world.

The dwarves were more skilled than the men of Morath when it came to working with metal and stone. But, unlike the Oronfal men, they chose not to exploit their talents for gain. Instead they treated their smithing like an art form, taking great pride in the strength and quality of their products. It was the nearest that the dwarves could come to expressing any emotion in their creativity.

Some of the soldiers wore crude armour made from sheets of tin shaped roughly around their bodies. Others had vests of chain-mail, heavy and cumbersome but undoubtedly effective in combat. As these dwarves walked their garb clanked and creaked, sounding like a multitude of rusty gates left swinging in the wind.

At the head of the column strode Sharmek, with Kirkmere, Askorn, Ilvar and other captains at his side. They would lead their followers northwards across Islanvir, the Green Glenn, past Mount Telquin and on to Tar Gelfay and the bridge to Oslar. There they would do whatever was necessary to safeguard the interests of dwarfdom and protect Ilis Clair from the ravages of men.

Not one among them doubted that there was a battle to be fought. It was something for which they had all been preparing in the past weeks and not to do so would have brought great disappointment. An army is for fighting, they thought, and Sharmek would not be leading them on this great journey if not to join in war.

Their minds had been changed so much of late that they often turned to thoughts of war when once they would have planned the sowing of crops or the mining of ore. And now they were actually setting off to take part in what would have been unthinkable such a short time ago.

The first day of marching passed with little incident. They strode onwards, rarely stopping for rest or drink. When they did halt finally for the night the sun was already well set. They made camp under the clear starry sky and lit great bonfires of brush wood and sang songs of killing and victory.

The early battle songs of the dwarves were crude and unmelodic. Theirs was not a musical race, but they would sing in their deep, gruff voices when the mood took them. What their chorus lacked in tune was more than equalled in volume. The ten thousand voices rang out for most of the night, though not always in unison, and they had no desire for sleep. At times they would practice their battle skills, cutting and thrusting into the air. Sometimes friends would make mock battle against each other and not a little blood was spilled in that manner during those hours of darkness.

When morning came bright and clear the dwarf horde set forth once more on their quest. They were an awesome sight; twenty thousand heavy boots raising the dust as they trod the north road towards the island of Oslar.

By noon of that second day they reached the village of Olindel. This was a small place inhabited mostly by men who had been friendly with the dwarves of Rimersel. They sold some of the ore and precious stones that the dwarves mined from the mountains and gave in return cloth, skins and food from various parts of the land.

The army that arrived that day was like nothing any man had seen before. They were all tired and hungry and descended upon the village like a plague. Dwarves seemed to come from every direction. The men of Olindel thought that it was an invasion force come to steal and destroy. Some of them ran this way and that, shouting warnings to their neighbours, whilst others hid in fear from the gathering crowd of strangers.

Sharmek had not intended to cause such alarm, but he chuckled a little to himself when he saw the effect that his troops had on the humans. So he called the elders of the village to meet him and he reckoned to have a little sport at their expense.

The people were led by a man called Ismark who was old and grey, but wise and stern. He greeted Sharmek and his followers as best he could, though he clearly doubted the good intentions of such a large band of travellers.

"Well Ismark," Sharmek began, "do you have food enough for my faithful friends?" He laughed in a cruel way that made the old man shudder.

"Dwarf Lord, you know that we could never feed such large numbers. And if we were able, it would only be on fair payment."

Ismark tried to show a little defiance, though he knew that he was powerless against such a force.

"Well is this payment enough," bellowed Sharmek, taking his axe in both hands and throwing it blade first into the ground at Ismark's feet. "I have had wind of the deeds of men hereabouts and I will not stand for insolence from one such as you. Be gone, and take your folk with you."

Sharmek flung his arms about him and Ismark took flight as best he could on his ageing legs. But the dwarf army seemed to take their leader's actions as some kind of signal and a kind of madness began to take hold of them.

Many of the dwarf soldiers took up their weapons and ran through the village, shouting and screaming at the tops of their voices. They herded the humans, men, women and children, out of their homes where most had been hiding in fright. Others kindled torches and began to set light to everything that would burn.

Some of the braver of the men took up spades and sticks and began to beat at the dwarves as they passed. One or two had swords or axes of their own and they wounded a handful of the attackers. But such actions only inflamed the violent passions of their assailants and the orgy of terror grew worse.

The dwarves began to make use of their weapons against their human captives. They ran through the groups of people hacking at them with their axes, wielding them round and round above their heads and chopping anything that came within reach. The red blood of men and boys ran along the dusty road and the washing holes were filled with the blood of their women folk.

Only a handful survived the terrible carnage and when the killing was done the dwarves piled the mutilated corpses into a huge mound and set them aflame. The Stinking bonfire burned for a day and a night and was a beacon of death seen throughout the south of Falforn.

As the fire burned the madness that had overtaken the dwarf army seemed to subside a little and some of them began to realise what they had done. Never before had such an atrocity been committed here and the blood of it would stain the land for many years to come.

Sharmek himself could not understand what had happened, or why, but he did not betray his true feelings to anyone. He had to remain the hard commander at any cost, so he carefully hid what little emotion was left within his shining armour.

The kingdom of Falforn was divided from neighbouring Oronfal by the great River Milfair, named after the large white birds that swam gracefully along its length. The river was a fast flowing waterway which had carried many a man and beast away to the south with its raging current. In its centre lay the long, narrow island of Oslar, home of Ilis Clair and looked on by many as the seat of all wisdom in the land.

Legend told of how Ilis Clair had been set upon the land before time itself began, and of how she had formed the mountains and the river, the forests and the glens. She had peopled the land too. She brought forth the dwarf folk first, making them from the rock of the mounts of Orosema, and then the Amarin, the Sandinid, the Topil, and finally Men. She had been helped by others though, the Zim Farinid, who had worked with their magic to mould the minds of the lesser beings and teach them how to live in the new world.

At the very north of the land the great forest of Gor Tarangarl spread from west to east as far as anyone had travelled. It was a dense, inhospitable woodland which seemed to change from day to day. No-one dared to venture far into those treacherous, tree covered slopes and valleys. Tales had been told of men and Amarin lost for days among the pines and elms, not knowing that the forest's edge was just a few miles away. Only the Sandinid could be found wandering freely in Clor Tarangarl, but they were the Green Men of the woods and were afraid of nothing that grew from the ground.

Near the western edge of Falforn stood the great mountain range of the Brondith, or West Rocks. This group of peaks was smaller than Oresema to the south, but none the less impressive. It lay along a line roughly north to south, almost cutting off the Temple of the Innocents and the town of Elm from the rest of Falforn. Only a narrow pass through the centre of the mounts gave access to those places, except for the long, arduous routes to the north and south.

At the southern tip of the Brondith stood the old ruins of Glowist. This had once been a magnificent castle; the pride of all the Storm Land, standing as it did at the centre of that kingdom, majestic and strong. But two centuries ago the ground had shaken with a mighty earthquake and reduced every dwelling in the area to rubble, including Glowist.

To replace that royal mansion the people built Noman Sith, the Glass Palace. That was further south, among the foothills of Golan; away, it was hoped, from the ravages of the trembling land.

To the north of the West Rocks, and only fifteen miles south of the Great Forest of the North stood the tall Sky Rock, Cliardith. This steep sided tor had long teased

the men who tried to climb it. For most of its history it remained unconquered, but eventually a road was cut into its side, winding round and around the craggy rock, rising ever upwards to finally reach its high summit.

Then they built a great fortress on the flat top. They called it Clarooth, Tower of the Sky, and from there the king of the day could survey much of his country and rule his people from high above.

The tower itself was tall, almost the height of a hundred men. It was stepped as it rose, each of the three terraces being narrower than the one before, although the citadel flared outwards slightly below each one. There were few windows in the thick stone walls, and these were only narrow slits. The wind at that height was strong and biting and sometimes the tower would be enshrouded by the lowest of the clouds. In truth it was a cold and forbidding place and only tradition stopped it from being abandoned as uninhabitable.

It was at Clarooth that Queen Rolquin held her flamboyant court. She was the reigning monarch of the line of Fornkayd, the Storm Kings, who had ruled Falforn since the first man had stepped from the word of Ilis Clair. In fact Rolquin claimed to be a direct descendent from that first human and a family tree had been drawn up tracing the line of kings and queens for ten thousand years into the past. Whether it was a true pattern none could say, but there was no doubt that Rolquin was the latest in a long line of royal descent.

The Queen herself was a powerful woman, quite able to command the men who assisted her in her sovereignty. She was in her fortieth year and had never taken a husband, though she had borne a daughter ten years ago to a father unknown to her people. Her looks were stunning and she did not show her age, looking always like a young girl with long flowing hair, a fair skin and a glint of mischief in her eye.

She was a clever woman who could not be tricked or fooled. She knew all that happened in her land and used her powers to the full. She would delegate little and often ignore the advice of her elders and advisers. She was a fair ruler, quick to reward but unforgiving if crossed. Her people liked her well enough and she took a keen interest in the ways of ordinary folk.

Sometimes Rolquin would dress in the clothes of a servant and walk among the commoners as they worked and played. She liked to hear the gossip first hand and see the effects of her administration on the people around her. She would listen to the stories they told, and watch the way they went about their work. She believed that it made her a better monarch to keep in touch like this, rather than set herself apart and never meet the commoners.

The Queen was dressed in this way when the news from Noman Sith arrived.

For several days there had been rumours circulating through the palace, though no news had reached the Queen's ears from official sources. They had started at the same time as a great wind had come upon them. That gale had raged for days, beating against the stone walls of Clarooth. No-one had dared to set foot outside because of its force and the biting cold that it brought.

When the wind had died down a little, messengers began to arrive. They brought news from many parts of Falforn, as was Rolquin's command. Much of it was mundane and uninteresting, but there had been some unusual sightings and happenings.

From Holath came news of a strange shooting star that had come with the setting Sun. At Ormead there had been a sickness that was claiming the lives of the Topil there. But it was the messenger from Noman Sith, the Glass Palace, who brought the worst tidings.

At first it started as a rumour. The women in the market hall were talking in low whispers Rolquin could barely hear what they were saying as they huddled together in small groups, jostling and pushing to hear the news.

"All dead they said," she heard one trader saying, "over a hundred, killed with battle axes."

"lt was the dwarves," said another, "a great army of them."

Rolquin could not understand what they were talking about. There was no dwarf army. They were a peaceable race. There had never been any trouble from the south of Storm Land. Who was it that could be dead?

She waited a little longer to see if there was any more information to be gleaned from the folk in the market, but in the general hubbub she could make out little. The people were becoming excited and the strange stories would soon become exaggerated out of all recognition.

The Queen made her way up through the Tower of the Sky as quickly as she could. The royal residence was at the very pinnacle of Clarooth and it was quite a climb. Stairway after stairway had to be ascended and each one seemed longer and steeper as she hurried to reach her throne room.

When at last she came to the state room, she paused at the door just long enough to don a long fur robe to cover her plain clothes. Then she entered the chamber and strode magnificently up the purple carpeted stairs to her seat of office.

A messenger awaited her.

"Well, what is the news?" she said, trying to hide her panting breath and arranging her long hair as she spoke.

"Your Majesty. I bring you tidings from Noman Sith," the courier began, removing his hat and bowing low before his Queen. 'I have been sent by the Marshal of the Glass Palace. Three days ago the royal guard were parading at the setting sun when a great madness overtook them. There was a mighty battle and everyone was slain, save the captain of the guard whose body has not been found. The scene was terrible to behold and the Marshal fears that evil work is afoot."

"The army was all slain you say?" Rolquin sat back in amazed shock. She could hardly believe what the man was saying; it all seemed too impossible to have really happened. After a few moments of silence she began to question the man. "Then who did the slaying? Was it the dwarves of Rimersel?"

"No your majesty, it was not the dwarves. There was no enemy in the battle; that is what the. Marshal cannot understand. The guard seem to have killed each other, though why we cannot say. No-one saw what actually happened, but there was no sign of another soul. There were none but human corpses, though they were hard to recognise, and all of them were from the guard themselves. There were no footprints of intruders nor clues of any kind. It was a foul deed and a great puzzle to us all."

"And what does the Marshal counsel?"

"He asks that an army be sent to Noman Sith to protect the palace from whatever evil has been set upon it. There are only a few soldiers left there, and no captain to command them."

"Very well," Queen Rolquin replied, "return then with this message. Say that I will send as many men as my guard can spare, and with all haste. He knows that my army is small and I can relinquish only a little of it. Reinforcements will follow as soon as can be."

With that the messenger bowed low again and departed from the throne room. Within a few minutes he was on horseback, speeding along the road to Noman Sith bearing the words of his Queen to his immediate master.

Queen Rolquin sat back in her golden chair and thought for a few minutes.

The state room was an enormous chamber at the very top of the Tower of the Sky. Its high ceiling was decorated with a superb frieze depicting the conquering of Cliardith and the building of the Tower itself. But the picture's bright colouring was almost lost in the dim lamp-light of the windowless room. Around the edges of the chamber tall columns supported the ceiling. These, together with the high walls, were also decorated, but this time with more abstract forms; geometric shapes, stylised animals and the like. The floor was bare stone except for a long strip of purple carpet laid from the main doorway to the throne itself, which was at the top of a short, wide flight of steps. At the door stood two guards dressed in shining armour and carrying long pikes. Apart from these two men Rolquin was alone, an almost insignificant figure in the grand throne room.

Suddenly the Queen clapped her hands. "Call for my council,"

she shouted, and at once one of the guards left the room to do as she commanded. Within a few minutes several men and women entered the throne room, each bowing

low as they came before the Queen. When all had assembled Rolquin motioned for them to sit.

Among those present were the Lord Chamberlain, Ilsarind, and Lairmath, captain of the Clarooth army.

"My loyal servants" Rolquin began, "I have grave news for you from Noman Sith, though I think you may have heard rumour already." Then she explained all that she had been told of the happenings at the Glass Palace, and of her reaction so far.

"I am sending one thousand of my men to Noman Sith. They are to leave immediately with you, Lairmath, at their head. Ilsarind, I expect you to provide me with an army ten thousand strong. They must be armed, provisioned and ready for me to lead them south within a week. The remainder of my regular army will stay here to guard this Tower. There are dark deeds afoot and we cannot afford to tarry in our response."

With that she signalled for them all to leave and go about the work that she directed. Lairmath went straight to his quarters where he donned his full uniform. He was a striking figure in his gold braided army tunic, taller than any other man in all of Clarooth and strong in mind and body. He was an ideal leader of men. They all looked up to him, both because of his height and because of the esteem in which they held him. He was popular throughout the ranks and his command would be followed to the letter since every man knew that it would have been made only after careful thought and judgement.

From his rooms the captain went to the barracks of the army. This large group of chambers was at the very base of the mighty Tower and took some time to reach. The men of Lairmath's army were stationed around the entrance way to Clarooth. The Tower had only one door to the outside world, a great wooden portal which had not been closed for many years, a fact which even now was preying on Lairmath's mind.

Just inside the entrance way was an enormous covered courtyard and around this Were the rooms that comprised the army barracks, armoury and stables. The soldiers of Clarooth were great horsemen and it was on this fact that their future might now depend. It seemed that great haste was called for and Lairmath intended to make the best use he could of their riding abilities.

When at last he reached the giant hallway of the palace he began to issue orders Some men were detailed immediately to repair the hinges of the mighty doors the had rotted and rusted through the years of disuse. He commanded that others should set off through the whole of the Tower and find whatever they thought could be used as weapons. The smiths should stop all other work, he said, save for the shoeing horses, and concentrate on the production of swords and spears.

He detailed his officers to muster a thousand men, over half the army, and had them ready to ride in one hour.

Then he left the courtyard again and set off for the upper levels once more. F wanted to say good-bye to his wife and there was very little time left in which to do this.

When the army of Queen Rolquin set off from Clarooth they were a magnificent sight. One thousand men of the finest cavalry ever seen in all Falforn rode quick out of the enormous gateway and down the winding road that encircled Cliardil They went at full gallop with banners unfurled and flapping in the wind. Their tunic were of the brightest red and gold and their badges shone as the sunlight glinted fro their upheld spears.

They rode on and on along the dusty road, gradually pulling further and further from sight.

At the head of the army rode Lairmath, his white stallion carrying him with ease as they sped across the foothills that surrounded the West Rocks. His long brow hair flowed out behind him and his halberd pointed upwards towards the sky.

Before too long though their pace slowed and they reduced to a trot, but still the travelled another five miles with every passing hour. The horses' pounding hooves stirred the dust as they went and behind the column of beasts and riders a great cloud rose into the air, which only dispersed an hour after they had passed.

By the end of that day they had passed the Temple of the Innocents, but they did not stop to pay their respects. Instead they camped for the night five miles to its south. It was a cold night since they had come without tents or shelters. They had nee for speed and were weighed down already with weapons and food enough for their journey to Noman Sith. The men endured it well though and at day break, after meagre breakfast, they set off once more.

On that day they passed by Elm. They filled their water bottles at its fountain an the townsfolk gave them whatever food they could spare. When they moved off again the people cheered and chanted.

"Long live the Queen," they called, and "Victory to the Army of the Storm Land.' But no-one knew what victory that might be, or even who they would be fighting if there was any fight to be had.

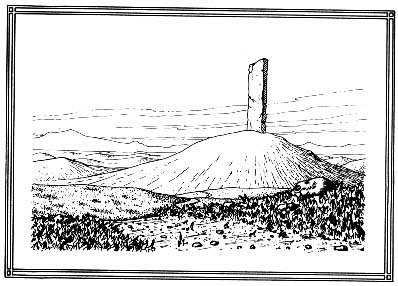

That night they all camped in the shadow of Amarnil. The old pyramid towered above the soldiers and their mounts, staring down at them as if it did not care about the way life had changed in its land.

No-one knew who had built Amarnil. It had stood since before men's history had begun, and even the dwarves had no recollection of a time when the edifice had no existed. It was a huge stone structure with no entrance and no windows. There were many stories about it but the truth could never be discovered. Some said that it was.'

the burial mound of the first dwarf lord, others that it was a machine that counted the years as they passed by. When at last time ran out the great building would collapse and bring down all the land with it. Another theory was that it contained the brother of Ilis Clair who had been entombed to contain the evil with which he had threatened the world in a far gone age.

Whatever the truth, it did not change the fact that it was a magnificent structure and a marvel of the ancient engineering that had produced it. Many an architect or builder still envied its fine lines and neatness of construction. The joints between the massive stones were all but invisible to the naked eye and its three edges were straight beyond compare. Only the wind and rain had eroded the hard rock and spoiled the meticulous design, yet it was still the greatest monument known to man.

That night was a little warmer than the one before. The great pyramid offered some shelter from the wind and the southern lands were always more temperate.

At dawn Lairmath and his men rode off again for the last day of their journey to Noman Sith.

Noman Sith, the Palace of Glass, was an oddity among the great buildings in this land. It was the newest of the royal palaces, both of Falforn and Oronfal, being just over a century old. It had been constructed in a variety of styles, taking a little from each of the previous mansions, and combining them all with the fashion of the time.

Its main theme was the glass and iron work that comprised the central hall. This was a wonder of its time. The smiths who wrought the metal had learned a lot from the dwarf craftsmen who, unusually, had given their knowledge freely. The men manufactured huge girders and columns, and built a latticework of iron between which they hung magnificent plates of glass, the finest that had ever been seen. But all this had been at great human cost. Many men had died in its making and the king of the time decreed that no other building should be erected in this style again.

The central hall of the palace was flanked on each side by tall towers of stone while its own arched roof reached a hundred feet into the air. Sometimes when a strong wind blew, huge sheets of glass crash down to the ground and the holes they left were almost impossible to repair. It took great skill to walk across the narrow roof beams to reach the gaping breaches, and then they could only be patched with animal skin or canvas. No glass could be brought to such a height now.

At the front of the palace a large paved terrace spread outwards. Its large hexagonal slabs were white for the most part, except in one area where they were newly stained brown by the blood of a terrible massacre.

It was here that Lairmath and his troops halted as the sun began to set at the end of their third day from Clarooth. As the great orange ball sank behind Noman Sith it shone through the glass of the palace, casting a huge geometric shadow across the courtyard, and scattering a myriad of rainbows on the flat stones.

When he saw them approach, Lord Frathel, Marshal of the Palace, came to greet the army.

"Hail Lairmath," he said as the captain dismounted, "your journey was swift."

"As the Queen commanded, my Lord," Lairmath replied. "We have been on the road for three days and halted only for darkness. Do you have lodging for my men, and stabling for the horses?"

"Aye, though simple it is for we had no time to prepare for so mighty an army. Some of your men may use the old barracks, we have little need for them now. The rest must billet in the great hall. For you, Captain, there are quarters in the south tower. Your horses must sleep under the stars, though that should not worry them overmuch."

With that Lairmath ordered all his men to dismount and see to their steeds. Only then could they rest themselves and feed upon whatever fare could be mustered. Sentries were posted and scouts were sent to spy out the land all around, though they could hope to find little before the sun set fully. Lairmath thought that Holdin Belanshar might still be close by, or that his body might be found.

When all was seen to, Lairmath himself retired for the night. He slept well in the feather bed that the Marshal provided and his room in the palace was warm and pleasant. He had suppered to his fill and drank a glass of wine, or two, and fell into a deep sleep as soon as he lay his head on the soft pillow.

He was awoken with a start. It was still dark and a guardsman stood over him with a dimly burning lantern. It took Lairmath a while to recover his senses, but when he did he sat up and spoke to the man.

"What is it? Is there trouble afoot?"

"There is a messenger, Captain," the soldier whispered in reply. "A man has come from Olindel bearing news of terrible deeds in that town. We thought that you should be awakened to hear his tale at first hand."

Lairmath arose immediately, quickly dressed and followed the man to the Marshal's chambers.

They found Erathel sitting with another man who was dishevelled and raggedly dressed. He had an open wound on his arm and was clearly distressed and shocked. And yet he had come nearly a hundred miles across the open plain without food or fresh water, drinking only from the rain puddles and animals' watering holes.

"This is Narlen of Olindel," began the Marshal. "He has come with a terrible tale. I think you should hear this Captain." Then he turned to the frightened man and spoke in a kind, soft voice, 'Now tell Lairmath what you have told me."

"Very well," Narlen began, his voice quavering with fear and horror as he remembered the terrible events. "It was yesterday, no the day before, that we were working in the smithy at Olindel; my father, brother and I. My brother was shoeing a horse, and 1 beating a scythe blade from a hot ingot. lt was around noon and we were about to stop to take lunch when there was a commotion outside.

"The village square was filled with people; not just men, but dwarves too. We all thought it very odd that there should be so many of the dwarf folk there. But soon we noticed that they were not craftsmen or traders, but soldiers. It was a huge dwarf army that had marched into town. They were all shouting, and pushing the men and women between them, laughing and teasing the people with their rough hands and cruel voices.

"My brother is... I mean was," he swallowed quickly and then continued. "My eldest brother was a quick tempered man and he set about a dwarf with his shoeing iron. At first the soldier ignored him, but suddenly he took out his axe and struck my brother with it. He took the blow full on his shoulder, and the dwarf's blade was sharp. My brother died in an instant and when my father rushed to help, he too was slain without a thought.

"Before long the dwarves were running amok throughout the village. They herded the men and women and then slaughtered them where they stood. It was an awful thing; I have never seen anything like it in my life, and wish to see no such deeds again. They killed even the children and the babies."

Then Narlen fell silent, hanging his head and sobbing loudly.

"And how did you come to escape?" Lairmath asked.

"I don't know, my lord. I jumped upon the horse, and rode off. The dwarves could not catch me, though some of them tried hard enough. One threw his axe and it caught me on this arm." He held up his left arm. The wound on it was long but not deep and the bleeding had stopped.

"I rode and rode," he continued, "galloping all the way without stopping. We must have gone for miles, until the animal could go no further. When I looked back I could see Olindel in flames and the dwarf army moving off once more along the I road to Oslar."

"To Oslar!" Lairmath stood up, hardly believing his ears. 'The dwarves intend to take Oslar and Ills Clair for themselves. I should have guessed that it was something of that sort. The dwarf folk have long since wished for power beyond their means, and they intend to get it with the aid of Ilis Clair. We must stop them before they destroy all that is good in this land. I'll wager that it was the dwarves who had a hand in the evil doings at this very palace."

Erethal spoke more quietly. "Calm yourself, Lairmath. You may be right, but we must not be hasty in our judgement. I would counsel that we wait for more word before we begin a war which we might never have the power to win."

"No," Lairmath spoke loudly, ignoring the words of his superior. "We must go at once and head off this column of death. To wait would be folly, and might bring our downfall more finally than a swift response in force."

He turned to Narlen, "How many dwarves were in this army?"

"I could not say," came the reply. "There were more dwarves there than I have ever seen men. There must have been a thousand at least."

Next morning a rider departed for Clarooth carrying a message for Queen Rolquin. It was written by Lairmath and carried his seal of office. It read thus:

"Your Royal Highness, I am in receipt of grave news from Olindel. A dreadful massacre has taken place there, perpetrated by a dwarf army from Rimersel. The dwarves are marching on Oslar and it is my belief that they intend to take Ilis Clair and use her against the human race. It is my intention to take eight hundred men and intercept them before they reach their goal. I would humbly suggest that you lead your army south east to meet us at the bridge across the Milfair. I remain your faithful servant, Lairmath, Captain of the Guard."

Erathel did not give his sanction to the Captain's decision, but neither did he try to stop him. It was not the Marshal's place to comment upon military matters and he considered that it would have been foolish to quarrel further with the Queen's own Captain.

Lairmath hoped to meet the dwarves before they reached the river. If they managed to cross onto Oslar, his small band of cavalry would be powerless to stop them. if they destroyed the bridge across the river he would be unable to reach them, and if they spared it they might be able to hold off any attack with ease. His only hope was in the speed of his riders, and he would press them to the limits of their endurance to succeed in his plan.

So eight hundred riders took flight from the Glass Palace. They took with them nothing but their weapons and they galloped with all their might to reach Oslar before the dwarf horde.

Lairmath led his men once more, but this time with a greater passion burning in his breast. He had vowed to himself that he would avenge the people of Olindel. He would make the dwarf army suffer in the same way as those poor folk had done. The earth creatures should be taught a lesson, he thought, and it was his task to see it done.

They journeyed along the eastern road, mostly going through the flat plain between Noman Sith and the River, a total of a hundred miles as a bird might fly, and longer by the road. But they could manage that distance in less than two days, perhaps even a day and a night if the sky was clear and the moons were full.

"If the dwarves left Olindel two days ago they might be at Oslar by now," thought Lairmath. "But they will be marching, and slowly at that. I think it will be a close race."

Sharmek Helm Head marched doggedly onwards, leading his troops along the north road, continually placing one heavy boot in front of the other, even though his legs seemed to have lost most of their strength. It had been a hard journey and his army was tired and restless. Since the incident at Olindel they had all been quieter, perhaps a little afraid of what they had done. Sharmek had feigned anger with his troops, but inwardly he was pleased with their performance. It proved to him, and to all those here, that the dwarf army was a powerful fighting force. And it was one which even men could not beat, for all their learning and wisdom.

They had come many miles since then and now their goal was almost in sight. They were level with the forest of Tar Gelfay, and the bridge to Oslar was just a dozen miles away. Its proximity tempted Sharmek and his captains, but they could push their soldiers no further without some rest. So they stopped at the eaves of the forest and rested a while.

They had not been still for long when they heard the blowing of a trumpet in the distance. They did not know what it was, and none among them could guess, but suddenly a great band of riders appeared over the horizon. It was an army of men.

Sharmek sprang to his feet. He called out, "Dwarves, arm yourselves. The enemy are upon us."

At once every dwarf fighter took up his axe, or whatever weapon he had brought. Most of Sharmek's army formed themselves into a great semi-circle in front of the forest's edge. Others retreated beneath the trees, to act as a rear guard. A few more advanced towards the human riders, swinging their axes and shouting for the blood of men.

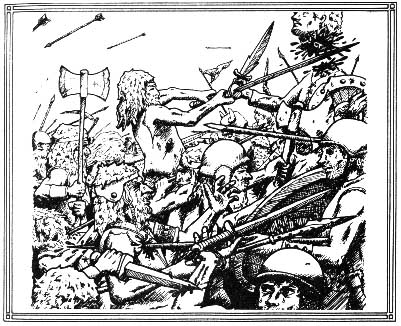

Half of Lairmath's men charged towards the dwarf enclave, their spears pointing forwards for attack. The others rode left and right, trying to trap the advancing dwarves in the jaws of their movement.

When the first of the foes engaged they inflicted heavy casualties upon each other. The dwarves suffered bitterly from the fast moving, horse borne attack. The men, and especially their horses, were killed by the dozen as the dwarves stood their ground and repelled the charge. Few of the advancing dwarves made any mark though. They were quickly out-manoeuvred by the skilled horsemen who weaved between them, turning this way and that and inflicting terrible injuries with their long spears.

Soon both sides fell back to count the cost; the dwarves to within the woodland and the men north, across the two roads that met nearby.

When the retreat was complete and all was quiet, Sharmek went forward again With a small number of his guard, to count the dead and assess their situation. He Was surprised that such a small number of men had inflicted such casualties on his troops, but he had not reckoned on the ability of the cavalry. They could out-perform a dwarf in all respects, except for steadfastness and physical strength. Yet these virtues were of little help if the enemy could outrun you in both the attack and retreat. Sharmek wandered among the corpses that lay on the muddy, hoof trodden ground.

He looked mostly at the dwarf folk who lay there. Some he recognised as loyal subject' some as friends, but all as members of his own race. He felt sad that life had come to this and that the old ways had been forgotten so easily. Then he turned his attention to the men, feeling for a moment just a little pity even for them.

Then he noticed the badges that they wore. These were not men from Oronfal an this was not the army of Theltiem. These were men from his own land. They cam from the north, from the army of Queen Rolquin. He realised at once his mistake He had led his dwarves north to fight a foe from another land. Despite the fact that they disliked all men, it had not been his intention to begin a war with the human of Falforn. Whatever he might think of them, they would have to remain his allies in the foreseeable future. The men far outnumbered the dwarves and to battle again' them would be extremely foolish. He realised that the fighting would have to stop if there was ever to be peace again with dwarves taking their rightful place in the world

Sharmek immediately sent forth an emissary to Lairmath's army. He knew that he would have to beg forgiveness from the Queen and he would lose her honour i doing so, but these were dark times and even Sharmek would have to suffer for the sake of his people.

So a lone dwarf, carrying a red banner, stepped gingerly forward, repeating in hi mind the message from his lord to the leader of the men.

"Sharmek Helm Head sends this message to you, my Lord," the dwarf said halting when the horsemen pushed him through their camp to Lairmath. "He asks that you show him mercy and forgiveness for the error of his ways. He says that his quarrel is not with the people of Clarooth, nor any in Storm Land. He bids that you meet him to discuss ways in which we may further our mutual interests. If you will come then I shall take your reply."

Lairmath thought for a long time without speaking. At last he said, "Very well take this reply to your master. I will come to meet him where the two roads join He may bring a dozen of his soldiers, and I will do the same. But be warned, m; army will be poised, and if I do not return within the hour, or send word, they will destroy all that remains of dwarfdom in this world."

With that the dwarf messenger was sent on his way and the captain of men prepare' to meet his enemy.

At the fork in the road Lairmath and Sharmek sat on the grassy ground to discus their alliance. Around them twenty four soldiers eyed each other with suspicion an' watched for trickery and deceit.

Sharmek spoke mostly and Lairmath replied to him only when he thought it necessary The dwarf leader told of how the men from Oronfal had taken control of Osla and were using Ilis Clair against them all. It was this power that had tricked the dwarves into killing the people at Olindel, and had forced these two allies into fighting against their will. He said that they should join together to combat the true evil force in the world; the men of Oronoman and the Amarin that aided them in their deeds.

Eventually, after giving it much thought, Lairmath consented to the dwarf's plans.

In any case, if what Sharmek said was true and the men from the east had conquered Oslar, then they would have to act to rescue Ilis Clair, for the good of all the peoples of Falforn.

And so the two armies reformed their ranks and began the last part of their journeys together. Lairmath and Sharmek went at the head of the line and their respective troops followed behind, a division of men followed by a similar number of dwarves, With the bulk of that army behind them. At the rear came the wounded of both sides. Those who could walk did so, and the rest were carried on the backs of horses or makeshift litters. The dead were buried within the bounds of Tar Gelfay, in two mass graves One for men, the other for dwarves.

But they were not a happy army now. Each side resented the decision of their leader and the dwarves and men looked on each other with disdain. Every one of them had 1~5t a friend or relation in the fighting, and they blamed each other for their losses. But they marched on since they knew it was all that could be done.

Before too long they came to the River Milfair, where the road crossed it by an old stone bridge.

The Milfair was a magnificent sight. Many of those present had never seen it before and they gazed in wonder at the rushing water as it sped past on its southward journey The river was nearly half a mile wide here and almost as deep, so it was said, and the current was so fast that no man could swim from one shore to the other. Only the bridges could be used to cross the mighty waterway, and there were only three of those, two from each bank to Oslar and one much further north, near Holath.

Slowly the military procession crossed the long, narrow bridge. They could go only six abreast and it seemed to take an age before all the men, dwarves and horses wen safely on the island.

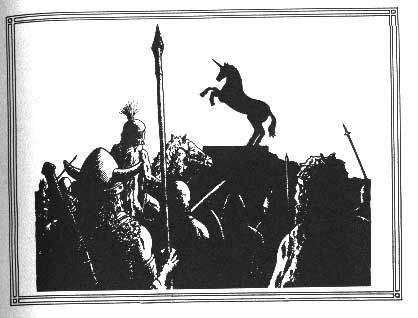

But the sight that met their eyes was nothing like they had expected. There was' no army from the east, no battle to be fought and no sign of evil work. Only Ilic Clair stood, as she always did, a fine sight outlined against the darkening sky. The Silver Singer. The Statue of the Unicorn.

Holdin Belanshar had left the Glass Palace far behind by the time he regained his senses. He had wandered aimlessly among the hills of Golan for many hours, not understanding his own thoughts and completely blind to all else around him. All the while he wrestled with his consciousness and for a long time he seemed to have no control over his mind, or his body. But every so often he would have a short respite, in which he momentarily saw himself as a small figure in a huge, empty landscape, before being overwhelmed again by the strange force.

Then, as quickly as it had come, the evil was gone and his mind relaxed in a sudden ecstasy of relief.

At first he could not believe what had befallen his men just a short time before, but he knew that he had seen it with his own eyes, and that the truth of the matter was more horrible than any nightmare. And now they were all dead, or so he presumed, and he was the only survivor. He wondered how it could be that he was still living. What force had saved him from the terrible madness that had overtaken the sane thoughts of so many men? He felt guilty for being the only refugee, and he was afraid for what might happen to him in the future. Perhaps the awful insanity would return and reap its revenge on him.

Eventually, in the dead of night, he stopped his wandering and sat down on a grass topped hill and wept. The tears ran down his face as if they would never stop and he remembered his friends and comrades who were now gone. He mourned for them all, and his life seemed empty and hollow without them.

But after a while he could cry no more and his mind began to turn to more logical thoughts. He tried to think clearly, to void his mind of the emotions that had almost consumed him, and to find a solution to his problems.

He could not go back to Noman Sith, that was certain. He felt that he would be blamed for what had happened. In fact he could not be certain that it was not truly his fault. It seemed too much of a coincidence that he was the only survivor. And because he was the only man left living, the others, his superiors, were bound to attach Some sort of blame to him. He was the commanding officer and should have been able to control his men, though he did not know how.

He did not really know what had happened, or why, and until that time he would never feel completely free. There was something in his mind which troubled him greatly, like the shadow of a stranger who cannot himself be seen. He had to find the truth of the matter and release himself from this mental bond.

As he sat in the cold night he decided that the first thing he needed was some shelter. If he could keep himself warm and find just a little food he might survive for longer and have time to think what to do. He could not remain here on these exposed hills for long.

When morning came he set off in a north easterly direction towards the southern end of the Brondith. He thought that he would go to the old ruins of Glowist. There Would be shelter there and he might find animals and edible vegetation too. He carried his sword and a knife, a flint to make fire, and a full water bottle. These would see him through for a short while at least.

It took him two days to reach the lower parts of the Brondith where the ruins stood He became lost on more than one occasion, only being able to use the sun for navigation and it did not shine for long each day. There were black clouds gathering and there threatened a storm, but it held off while he was travelling, something for which I was most grateful.

Holdin was a short, stocky man of great strength, both physical and mental. While in the Palace of Glass he would exercise to keep his muscles firm and powerful, an he would hold long philosophical discussions with his close friends and companion He and the Marshal of the Palace would play games that taxed their minds and each would try to outwit the other in methods of strategy and tactics.

Belanshar was unusual among the captains of the army; he had risen through the ranks to reach this position, whereas most seemed to gain such honour by inheritance or luck. This man had worked hard though, starting as a foot soldier and treading the beat of a palace guard for many years before eventually being promoted to lieutenant From then on life had been a little easier and when his predecessor died Holdin had been the Army Council's unanimous choice for the post.

It was the Army Council that decided on the overall day to day running of the army of Falforn. Only they stood between Holdin and his peers and the Queen herself Yet the Council had no say in the strategy of the army and the three captains of the Storm Land were in command. Only Rolquin could interfere in such matters, which she often did.

When at last Holdin came to the ruins of Glowist the dark clouds had parted an allowed the sun to break through with fleeting beams of brilliant light. It shone brightly against the peak of Molaktar, the southern most point of the Brondith, and the the covered mount seemed to glow with a spring green of new growth.

The ruin itself was much as it had remained for the last two hundred years. For the most part it was just a huge pile of rubble. Great square stones that had once formed the most regal castle in all Falforn were now piled here and there in tall, shapely mounds. What had once been shining towers of marble were now heaps of crumbling rock that glinted in the sunlight like a million shards of broken glass.

Yet the destruction had not been absolute. Here and there amongst the broke fragments a shelter could be found. Perhaps a room not totally crushed by the force of the earthquake, or a recess created as the stonework fell in upon itself.

The captain strode wearily across the undulating plain towards the ruins. He was tired and hungry. He had not slept since the day of the massacre, and food had bee scarce on his wanderings. Once he caught a rabbit and roasted it on a spit. Another time he found a soylok bush loaded with fruit. He had picked the red berries as though they were the last food in the land, and when he had eaten his fill he brought wit] him as many as he could carry. But a man cannot live on sour fruit alone and hi stomach ached from a surfeit of them.

Finally he came close to the old castle. In an instant something knocked him bodily to the ground. It was as if a great weight had come hurtling towards him and pushed' him backwards onto the hard earth. Yet he had seen nothing, and there had bee no sound.

And worse was to come. He found that he could no longer stand up at all. The invisible weight seemed to have landed full on top of him and he could not push it aside, though he tried with all his might. it was impossible to even lift an arm or a leg under the force, and the immense pressure seemed to push him into the firm ground where he lay.

eThen there came the voice. It was a hideous, ugly voice that hissed out its words

eand seemed to spit into his ear, like someone whispering into a dream.

"Who are you?", it said. "What brings you to the ruins of the Old House?" d Holdin could not answer though. There was barely enough air in his lungs to breathe; he could spare none for talking.

The voice repeated its questions, and then the heavy pressure eased a little and the man was able to rasp out a reply.

"I am Holdin Belanshar, I mean no harm, 1 did not knowingly commit the crimes of which you accuse me. I am an innocent man."

He almost pleaded with the unseen adversary, and though it charged him with nothing, the guilt that welled within his own mind made him say things that he did not mean to.

"Then why do you come here?" continued the voice.

"I seek only shelter from the elements. I mean no harm to you, or any living soul. I wish to find help for myself, and my people. There are questions to be answered, and I cannot find a way to do so. I need time to think and be alone."

Suddenly the mysterious weight was gone and Holdin found that he was able to stand again. He breathed a deep sigh of relief, then filled his lungs again to counter the effects of the crushing they had received. Then he realised that he was alone and he began to wonder what had happened, and who the invisible creature might have been.

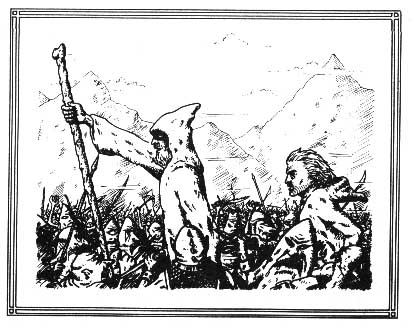

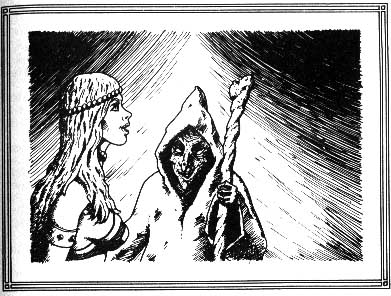

He was about to set off towards the ruins once more when a man appeared over a gentle ridge in his path. He recognised the figure at once, not because he knew him but because he had heard of his kind and knew of them well. This was not a man at all that walked slowly towards him, it was one of the higher mortals, the Zim Farinid. Holdin could tell by the way he walked, the slow stooping gait, and by his clothes, and the staff that he carried.

The old man wore a grey robe that came almost to the ground, and a tall hat that covered most of his head and face. His long wooden staff was old and gnarled; it looked as if he had used it to walk for a thousand years, and always along the most dangerous paths. His face, though old and lined, was kind and welcoming.

Holdin had never met one of these old wizards, but he had heard many tales about them. He knew how they had helped Ilis Clair to shape the land, and to teach the men and other creatures how to live in it. They had saved the world from the creeping Plague and even now watched over all things to see that no evil could overwhelm the peaceful life that they all enjoyed. They were a kind and benevolent race who Would harm no-one and brought only good to all they met.

"Good morning to you, sir," the soldier called out, almost amazed to see him there.

"Good morning you call it," the old man replied grumpily, "I would call it no more good than a cold wind on a summer's day. What brings you here to trouble me? Cannot the men of this world leave me in peace? Have I not done enough to help your lot that I must be bothered at all times, whether I wish to assist or not?"

Holdin was a little taken aback by the mighty one's attitude. He had expected soft talking and swift aid, but it seemed that he was wrong, and that all the old stories he knew had confused the real nature of this powerful race.

"Forgive me, sir," he said, hanging his head. "I meant no harm to you, and I did not wish to bother you with my problems. I did not seek you out, but came here by accident. If you will let me on my way then I will go and leave you to yourself." He turned as if to go, but the old man called after him.

"Holdin," he said, "do not trouble yourself with my ramblings. I see that you are in need of rest and shelter. Come with me and I will help you as best I can. I'll warrant that a good meal would not go amiss.

With that he turned and beckoned that Holdin should follow.

They walked solemnly over the low hills to the old stone ruins. Holdin followed

a few paces behind, perhaps a little afraid to come level with the old man. He was

held somewhat in awe of him and he dared not risk his disfavour. He seemed to have